By

Jake Fleisher

What is a diary study?

A diary study is a well-known, established methodology that has research participants making regular notations about specific topics over a period of time. It’s a great way for participants to record their unsolicited thoughts, to gather feedback over time, and to provide a foundation for future or follow-up research work with specific participants.

In the “old days” participants would keep physical diaries making entries in a notebook as often as they like or as the study requires. These days, diary studies can be much richer and more flexible by taking advantage of digital, connected technologies. At Blink we’re developing a suite of internal digital tools that help researchers and designers be more effective; one of these tools is our Digital Diary.

Advantages of the digital diary

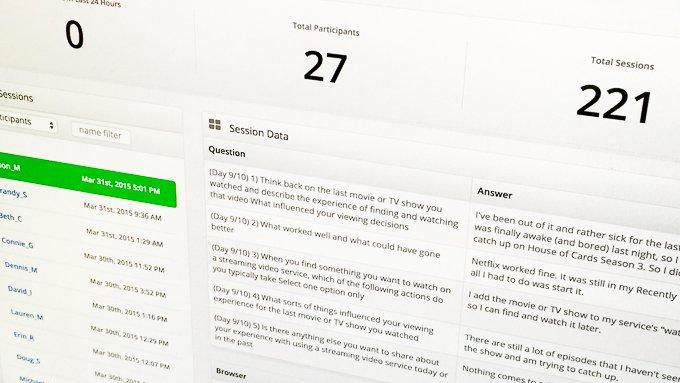

The Digital Diary takes the diary methodology to the next level, improving ease-of-use, depth of information, and participation levels for both researchers and study participants. The Digital Diary forgoes the requirement of carrying a notebook with you; the Diary lives in the cloud and is accessible at any (connected) time, on any device, by both researchers and study participants.

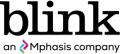

Participant entries are far richer with the Digital Diary—for each study, we create a custom form according to the study requirements. This can include any number of multiple-choice and open-ended question fields. Participants can easily upload screenshots, photos, and location information where appropriate. One of the newest features we’ve built is messaging ability within the Diary tool. With messaging, researchers can ask participants about specific entries (for clarification, more information, etc.). And because participants can easily answer within the tool, they’re more likely to make timely follow-ups on researchers’ questions.

The Digital Diary is also much more flexible. With hard-copy diaries, participants were constrained by the need to carry their diary with them with only one way to record entries. Researchers would have to wait before they could view diary entries. The Digital Diary is flexible and designed to be responsive—participants choose the platform and channel that’s right for them: desktop, laptop, tablet, phone, WiFi, cellular, etc. This flexibility helps participants record entries in-the-moment, instead of waiting (and potentially forgetting important details). Researchers get to view entries in real time instead of waiting days or weeks to get information or assess participants’ fit for the study. We’ve also added features in the Digital Diary that help us keep track of the participants and their engagement levels—auto-reminders help participants keep on top of their entries, and text- or email-based alerts let researchers know when participants have updated their diaries.

Our Digital Diary is a new tool for our research work at Blink, but we’ve already seen a big increase in studies where clients are interested in using it. A distinct advantage is that it can easily extend the period of time we gather information about users with less impact on budget. The extra information we receive is useful in many ways, one of which is to add another level of “previewing” research participants before we get them in the lab for a usability session, or go to their home or work for contextual interviews. If a participant is particularly engaged (or not), that has significant influence on whether we want to talk to them further, or choose someone else for follow-up work.

Future implications

We’re still learning the best ways to use and implement Digital Diaries. We’ve found it’s important to manage participant on-boarding, monitoring and responses, especially for studies with larger numbers of participants. As a general rule, we split participants into groups of 10 to 15, and assign one researcher to each group of that size. This way, it stays manageable and nobody gets “lost.” Researchers get together semi-weekly to review and compare their participant groups, and to trade information, questions, and tips.

Another thing we’ve found when running a diary study is that it’s important to provide an initial “human touch,” actually calling and talking to participants to offer help or to answer initial on-boarding questions. We’ve found that participant engagement increases substantially when they know there’s actual human interest (not just a faceless website) in their diary entries.

We conduct plenty of international research studies at Blink, and an international Digital Diary has to be approached differently than a domestic study. In a current Digital Diary study with both domestic and international components, we gather location information (with participant permission) for each diary entry in the U.S., but we can’t do this in Japan or Germany (even with participant permission) because of these countries’ privacy laws. It’s important to set expectations with our clients first, that across all participants, the research data fields may not be entirely consistent.

Diary UX

It’s no surprise that the visual design, interaction design, and overall user experience of the Digital Diary tool is important. Things like friendly user names, and ease of login and entry submission contribute to increased participant engagement and a successful study. Diary UX can make or break a participant’s desire to use the tool or not. We suspected, and have seen, that how we design diary study questions (copywriting and layout) can also have an influence. It’s important to write questions in a way that helps guide and remind participants of the study’s goals. A balance of multiple-choice with open-ended questions is helpful, and good copy helps participants focus on the study goals, instead of inputting information that may be interesting but out-of-scope.

Gauging the last two quarters’ studies at Blink, we expect to see even more interest in using the Digital Diary as we move forward: it’s an almost real-time, asynchronous method of gathering research participant needs, habits, and attitudes, with minimal “interference” from researchers. For studies that have a follow-up component, it’s a great way to identify qualified study participants who you know will provide engaged feedback in the study’s area of interest.

Jake Fleisher practices research and design at Blink, and has experience in product development strategy, hardware+software UX, field research, and nighttime bicycle rides.